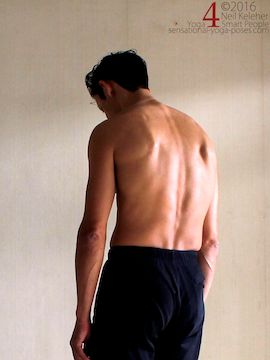

While reverse breathing, the lower back expands while inhaling. This generally means the lumbar spine flattens (or straightens) and as a result the back ribs can feel like they are lifting or moving away from the back of your pelvis.

While exhaling the lumbar spine resumes it's "natural" backbend or "lordosis".

Anchoring the Front of the Ribcage

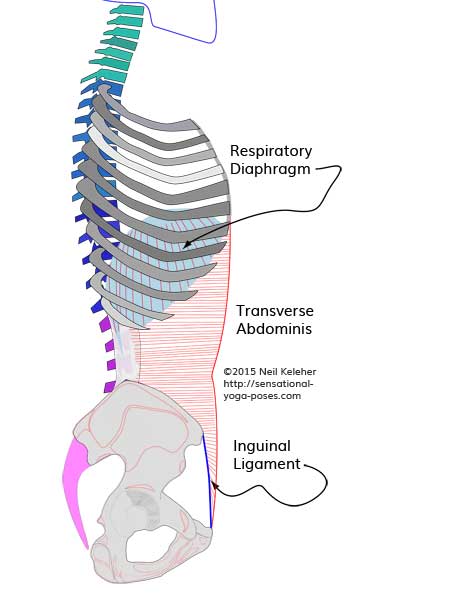

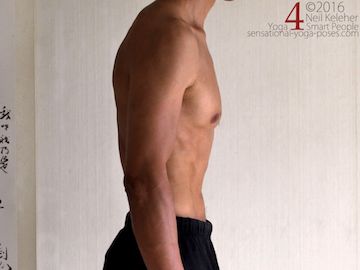

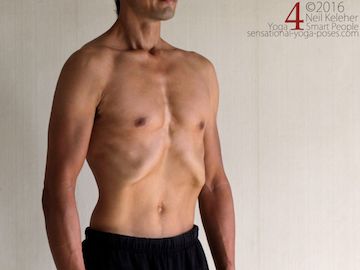

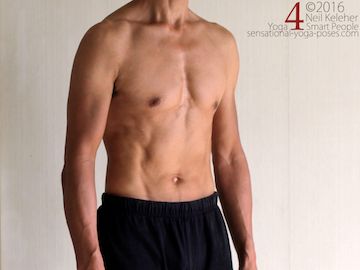

While reverse breathing the obliques (and possibly the transverse abdominis and rectus abdominis) are used to anchor the bottom rim of the ribcage, particularly the front part, so that it doesn't lift. This then anchors the portion of the respiratory diaphragm that attaches there.

As the diaphragm activates, it presses down on the abdominal organs. Because the front of the ribcage is anchored, by the abdominals, the back part lifts. Helping to cause the lumbar spine to straighten (or at least that is what it can feel like!)

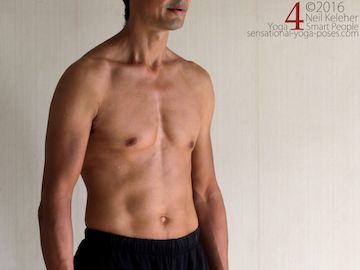

What may then happen (I'm not positive on this) is that both the quadratus lumborum (which attaches to the back of the pelvis and from there to the transverse processes of the lumbar spine (l1-l4) and the twelfth rib on each side) and the rear-middle fibers of the respiratory diaphragm activate together.

Lengthening the Quadratus Lumborum

The quadratus lumborum pulls down on the 12th ribs while the respective fibers of the diaphragm pull upwards on it. During the course of the inhale when the focus is on expanding the lower back the diaphragm exerts a slightly greater force than the quadratus lumborum.

Since the front of the ribcage is anchored the added tension to the diaphragm pushes upwards on the bottom of the back of the ribcage.

Because the diaphragm is exerting more force than the quadratus lumborum, the quadratus lumborum gradually lengthens allowing the rear of the ribcage to lift upwards away from the rear of the pelvis.

It may actually be the case that the whole diaphragm is active in this action otherwise there might be "leaks" places where the diaphragm gives in. However, it may be the case that certain fibers are more active than others.

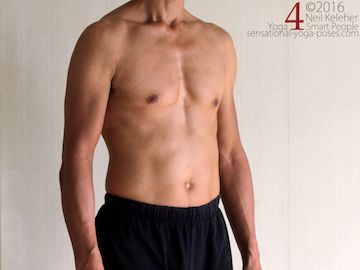

The Exhale Phase of Reverse Breathing

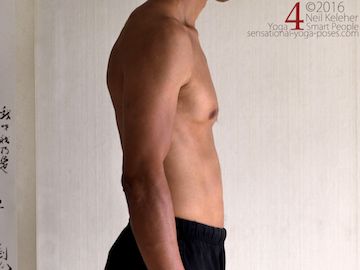

For the exhale, the tension in the diaphragm can be gradually reduced so that the rear of the ribcage sinks down due to gravity or due to residual tension in the quadratus lumborum. There may be a corresponding slackening at the front of the belly since the rectus and/or obliques don't have to exert so much effort to keep the front of the ribcage anchored.

This is my best guess as to what happens based on my experience and understanding of reverse breathing. I'd suggest using it as a starting reference.

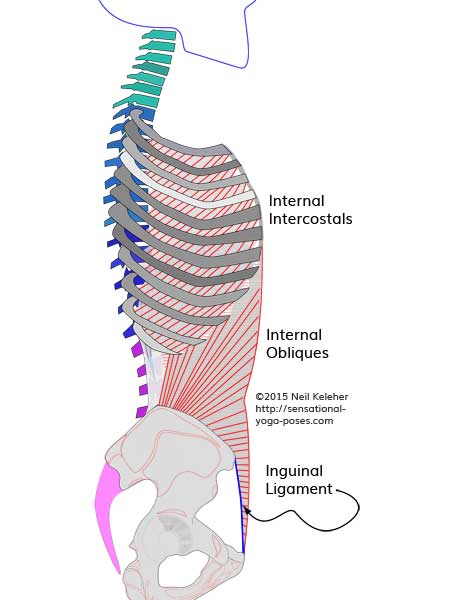

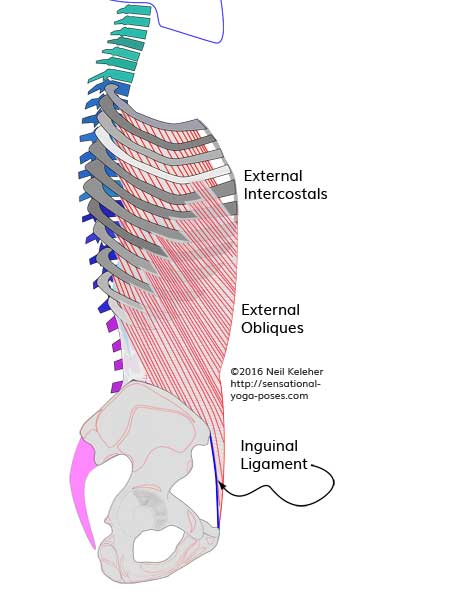

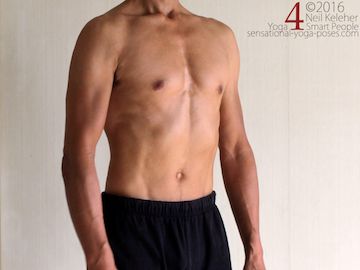

On further feeling around, I'd suggest that it is the more forward fibers of the internal and external obliques that activate to keep the front of the ribcage anchored. But it may be that the transverse Abdominis also activates to pull in the belly while the external obliques activate to keep the fronts of the lower ribs activated and the internal obliques activate to negate the forward pull of the external obliques on the ribcage.

The external obliques create a forwards and/or downwards pull on the ribcage relative to the pelvis. The internal obliques can be used to create a rearwards and/or downwards pull on the ribcage. The intercostals may also be involved for further stabilizing of the ribcage.

Also note that if the transverse Abdominis are activating, particularly the lower fibers, the pelvic floor muscles may also activate to stabilize the pelvic bowl via the SI Joint.