Transverse Abdominis training, toc

To activate your transverse abdominis, pull your belly inwards past the border of your ribcage and pelvis. Do this without allowing your ribcage to lift.

- When you pull your belly inwards using your transverse abdominis you should cause an exhale.

- Relaxing your transverse abdominis so that your belly expands, you should find that you naturally inhale.

As mentioned in the introduction, some people tend to pull their ribcage up to cause their belly to suck in. This is generally (I'd dare to say "always") accompanied by an inhale. How do you get around this tendency?

One way to get around the tendency of pulling your ribcage upwards to "suck your belly in", is to pull the front of your chest downwards. You can do this prior to pulling your belly in, or at the same time.

As a side note, when you pull your front ribs down, one of the things you can notice is that your thoracic spine bends forwards. You basically go into a "slouch". Then, when you allow your front ribs to lift, you "de-slouch".

Slouched with front ribs descended

De-slouched with front ribs lifted

If you sequence the two actions, you should find that pulling the front of your ribcage down causes you to exhale. Then, when you pull your belly in, you continue to exhale.

Chest slightly lifted,

belly relaxed.

Chest slightly descended,

belly pulled in.

You can then relax both actions, allowing your ribcage to lift and your belly to expand to cause an inhale.

Practicing Transverse abdominis activation in isolation

Once you get used to exhaling as you pull your chest down and belly in, you can then work towards keeping your ribcage still as you pull your belly in so that you can practice transverse abdominis activation in relative isolation.

You can practice this with your chest lifted (and while keeping it lifted). You can also practice with your chest descended (again, keeping the chest descended). And you can practice with your chest neutral.

Defining Neutral chest lift

A neutral chest lift position could be defined as a position where your chest is comfortably lifted, enough that you can easily balance your skull over your ribcage without undue neck muscle effort.

One way of training yourself in both feeling and controlling your transverse abdominis is using while breathing. You can activate your transverse abdominis to cause an exhale and then relax it to inhale.

Once you are used to activating your transverse abdominis to drive an inhale you can use this in various breathing patterns.

Some sample breathing patterns that can be used for transverse abdominis training include:

- Activating transverse abdominis to cause an exhale

- Relax to allow an exhale

- Activating transverse abdominis to cause an exhale

- Expanding ribcage to cause an inhale

- Relax both actions to exhale

- Expand ribcage or chest to cause an inhale

- Pull belly in to cause an exhale

- Relax both actions to continue the exhale

- Actively expand your belly using the respiratory diaphragm to inhale

- Pull your belly in using your transverse abdominis to cause an exhale

For more breathing pattern options check out the sensational breathing exercises page.

When you pull your belly inwards past the border of your ribcage and hip bones, you'll actually be using your transverse abdominis to lengthen the overlying obliques and rectus abdominis. You could think of this as actually stretching them.

So as you contract your transverse abdominis past the border of ribcage and hip bones, you are lengthening your obliques and rectus abdominis. This is particularly true if you prevent your ribcage and hip bones from moving as you do this.

As you use your transverse abdominis to lengthen the obliques and rectus abdominis, they will activate to resist being stretched. You are thus exerting your transverse abdominis against your obliques and rectus abdominis.

Advantages of using the Transverse Abdominis against the other abdominal muscles

Using the transverse abdominis against the other abdominal muscles has several advantages:

- This opposing muscle activation creates sensation that allows you to feel your belly as you pull it inwards. At the same time, it stabilizes your mid section.

- It gives you greater control of your transverse abdominis.Working against the resistance of your obliques and rectus abdominis, you can control the rate at which you pull your belly inwards.

- It gives you greater control of obliques and abdominis rectus. Via transverse abdominis tension you can adjust the length of the other abdominals for optimal function.

- Since the transverse abdominis works on the SI joints, the lumbar spine, the bottom half of the ribcage (and the thoracolumbar junction), when you activate your transverse abdominis, you get lumbar, thoracolumbar junction and SI joint stability all for free.

For that last point, another way of putting it is that these three regions could be considered as "the lower back".

And so with transverse abdominis activation, if you use it to pull your belly past the border of ribcage and pelvis,

you get lower back stability for free.

Because of the horizontal orientation of the fibers of the transverse abdominis, you can activate it easily and keep it activated no matter what your spine is doing.

So even while you are bending your spine or twisting it, or simply keeping it neutral, you can activate your transverse abdominis, or keep it active.

Because of this, you can vary tension of the transverse abdominis to maintain operating length of the other abdominal muscles so that they can activate effectively when required, no matter what the spine is doing.

A very basic transverse abdominis training exercise is to practice activating and then relaxing it in isolation.

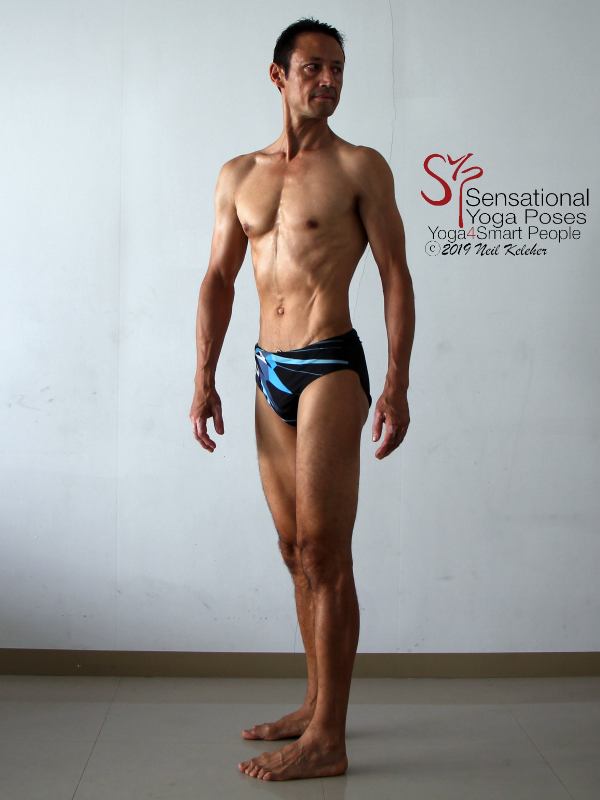

While standing (with knees slightly bent to begin with) or sitting comfortably upright, slowly pull your belly in. Pause. Then slowly relax your belly.

Transverse Abdominis relaxed.

Transverse Abdominis activated.

To begin with, focus on keeping both your ribcage and your pelvis stationary while doing this.

I'd also suggest inhaling and exhaling through your nose.

When you pull your belly in, you should cause an exhale.

When releasing your belly, you should find yourself inhaling.

If you want to work at holding your belly pulled in, then allow your chest to lift and lower as you inhale and exhale.

You can practice activating and relaxing your transverse abdominis while doing a standing side bend. Adjust the forward and backward tilt of your ribcage and hip bones so that your hips and lower back (and all other parts of your spine) are comfortable, and then maintain that position while activating and relaxing your transverse abdominis.

Don't be afraid to adjust the front/back tilt of your ribcage or hip bones.

An adjustment is a slight change in position. And actually, it can be repeated slight changes in position, like moving a radio tuning know one way and then the other, repeatedly to find the position of "best reception".

Try standing side bend with arms down first, it can make it easier to activate your transverse abdominis.

When reaching, push hips further to the side for balance. Work at keeping your transverse abs engaged.

You can try the same transverse abdominis exercise in a standing twist. With feet parallel or slightly turned out, turn your pelvis, and your ribcage and your head. Pull your belly in and see if you can deepen your twist gradually.

Once you get used to keeping your transverse abdominis engaged in the standing twist, work at lengthening your sacrum, lumbar and thoracic spine to give them "feel". Use the feel, which is generated by activated muscles, to deepen your twist.

When pulling your belly inwards using your transverse abdominis, you can always allow your pelvis to tilt back as you do so. Or, as in some of the previous exercises, you can deliberately pull up on the front of the hip bones (the pubic bone and ASICs). Another option is to focus on feeling the back of your lumbar spine flattening as you tilt your hip bones back.

The basic movement is the same. What changes is what you focus on "feeling" or "sensing".

The funny arm position in both the above two photos is so that you can see my lower back, both the normal curve in the first photo and the relatively flattened curve in the second.

On all fours you can try the same action, using your transverse abdominis to draw your belly in so that your lumbar spine flattens.

Once you can do this comfortably, try lifting your knees after a full contraction.

You'll have to look closely to see that in this picture my knees are actually lifted.

A good test of general awareness and control is to try to lift your knees just clear off of the floor.

From all fours, another option is to step back to plank after having activated your transverse abdominis.

It can be difficult to activate your transverse abdominis while you are in plank. The following steps can make it easier to activate your transverse abdominis and then keep it active as you move into plank.

The steps are:

- Pull your belly in

- Protract your shoulder blades

- Keep your ribcage and pelvis still as you step one foot back at a time.

Hold for a few breaths, then release and repeat.

Step your feet back slowly, so that it is easier to keep your torso still and your transverse abdominis engaged.

Anchoring the hip flexors

One way that the transverse abdominis can be used in combination with the other abdominals is to anchor the hip flexors, in particular the long hip flexor muscles.

These are the hip flexors that work on the knee as well as the hip and include the tensor fascia latae, sartorius, rectus femoris and maybe even the gracilis.

The latter three all attach at or near the ASICs while the gracilis attaches to the pubic bone.

Prior to learning how to anchor these hip flexors, it can help to get a feel for your ASIcs and pubic bone.

When you activate your transverse abdominis you may be able to notice that your hip bones to tilt backwards a slight amount. When you relax, the opposite movement occurs.

To make this action easier to notice, you can focus on prominent landmarks like your pubic bone and ASICs (the "points" of your hip bones.)

When you pull your belly and your hip bones tip back, your ASICs and pubic bone lift. The opposite happens when you relax.

This is all due to tension that is added to the other abdominal muscles when transverse abdominis is activated.

Once you can notice these landmarks, we can try anchoring them by deliberately pulling them upwards.

To create a strong upwards pull on the front of one or both hip bones, you can experiment with lifting your chest first. Keeping it lifted, pull your belly inwards. Then, keeping your chest lifted and belly pulled inwards, pull up on your ASICs and pubic bone.

While it can be easy to assume that the higher you lift your chest, the stronger the upwards pull you can generate on your ASICs and or pubic bone, play around with varying the amount of lift you give your ribcage.

Initially, try lifting your chest maximally, as high as possible, and then, subsequently, prevent your ribcage from moving while activating your transverse abdominis and then creating an upwards pull on ASICs and pubic bone.

Then try it with the chest only moderately lifted.

Once you have a feel for that, the next exercise is to lift one knee while maintaining the upwards pull on ASIC and pubic bone (and while keeping chest lifted and transverse abdominis engaged).

Stand with your weight on one leg with foot comfortably turned out and knee slightly bent. Lift your chest. Then pull in your belly. Then pull upwards on ASICs and pubic bone. Then lift the knee slowly towards your chest.

As you lift your knee higher you can increase the amount of lift on the ASICs (on the lifted leg side) as well as the pubic bone.

Repeat a few times and then change sides.

In the starting position my weight is over my back foot!

Note that with my leg lifted, my pelvis isn't level.

I'd suggest adjusting not for a level pelvis but so that both sides of your belly (and your lumbar spine) feel even.

Something you can experiment with is to lift the pubic bone and ASIC higher as you lift your knee. You could also experiment with pulling your belly in further as you lift your knee higher. Another option is to try and lift your chest higher as you lift your knee higher.

A variation is to straighten the knee after lifting it. Or alternatively, lift the leg with the knee straight.

Note the sartorius activation.

Particularly when lifting the leg with the knee straight, make sure that you activate your transverse abdominis first. Then, to make it easier to keep the action, gradually lift your leg while keeping the knee straight.

The standing knee can be bent or straight!

Repeat this basic hip flexing exercise with your chest lifted to varying degrees to find the optimum amount of chest lift.

Lying on your back with knees bent and hips lifted for bridge pose, here too you can pull your belly in to activate your transverse abdominis.

Take some time to notice the sensations that occur in your lumbar spine but also at the lower "rim" of your ribcage.

With your belly pulled in you can work at lifting your hips higher or otherwise deepening your spinal backbend.

One way to deepen your awareness and control of the transverse abdominis is to divide it into three bands and practice controlling these three bands in isolation so that you can better integrate them. Advantages can include SI joint stability, lower ribcage and thoracolumbar stability and lumbar stability in general. Read more in transverse abdominis exercises.

For a fairly detailed overview of how the transverse abdominis can interact and affect (and be affected by) related muscles and body parts check out the transverse abdominis article.

For a potential exercise in frustration, try the second version of agni sara, explained in agni sara. It's an exercise that involves sequentially activating (and then relaxing) adjacent bands of the transverse abdominis. The subdivisions of the muscle used in agni sara are more than the basic three covered in the transverse abdominis exercises page. If you like puzzles, then agni sara might just be your cup of tea.

Published: 2019 08 08

Updated: 2021 03 23