Sacroiliac Joint Ligaments and Muscles

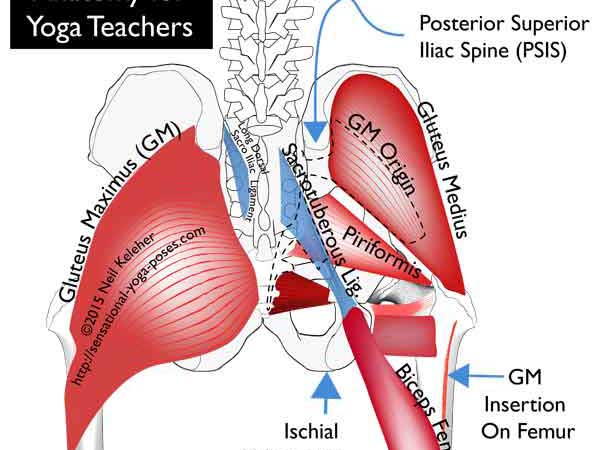

With regards to the si joint, ligaments aren't passive structures that create tension only at the extremes of motion. Instead the ligaments of the sacroiliac joint can be affected by muscle tension. The main ligaments we can be concerned with are the sacrotuberous ligaments and the long posterior sacroiliac ligament.

Muscles that can affect the sacroiliac joint via these ligaments include the sacral and lumbar multifidus, lumbar spinal erectors, gluteus maximus, piriformis, biceps femoris long head (and possibly the other muscles of the hamstrings group including the semimembranosus and semitendinosus).

The latissimus dorsai can also have an affect on the Sacroiliac joint since it has fibers that cross the SI joint and blend with fibers from the opposite side gluteus maximus.

Other muscles that can directly affect the sacroiliac joint include the lower fibers of the transverse abdominus and the pelvic floor muscles.

Basic Movements of the Sacroiliac Joint

Before we talk in more detail about the muscles that can affect the sacroiliac joint and their relative stability it helps to understand the basic movements of the sacrum relative to the pelvis and the affect these movements have on the shape of the pelvis.

Assuming the sides of the pelvis to be fixed so that they don't rotate forwards or backwards, the sacrum can nod forwards relative to the pelvis or it can nod backwards.

- The forward nod, termed nutation, moves the top of the sacrum forwards and the bottom of the sacrum (the tailbone or coccyx) rearwards.

- The backwards nod (contra or counter-nutation) moves the top of the sacrum rearwards and the bottom of the sacrum forwards.

The forward nodding action of nutation not only moves the top of the sacrum forwards, it causes the ASISs, the point at the front of each crest to move inwards so that the uppermost opening of the pelvis gets smaller. At the same time, as the tailbone moves rearwards, away from the pubic bone, the two sitting bones move outwards so that the bottom opening of the pelvis gets larger.

The rearward nodding action of counter-nutation does the opposite. It increases the size of the uppermost opening of the pelvis by moving the top of the sacrum rearwards and the two ASIS outwards. Meanwhile the bottom opening of the pelvis becomes smaller (tighter) as the tailbone moves forwards towards the pubic bone and the two sitting bones (technically "ischial tuberosities" or ITs) move inwards.

Both of these movements can be driven by muscular contraction.

Muscles that Directly Control the Sacroiliac Joint

The lower fibers of the transverse abdominus, which connect the fronts of the two halves of the pelvis at the ASIS and the inguinal ligaments, can be used to pull inwards on the ASISs, causing them to move inwards. The sacral multifidus can also be used to "flick" the tailbone rearwards. Together or separately these actions can cause the sacrum to nod forwards relative to the pelvis, causing the tailbone to move rearwards and the ITs (ischial tuberosities or sitting bones) to move outwards.

The pelvic floor muscles, which as a whole connect the tailbone to the pubic bone as well as the lower inner rim of the pelvis bowl, can be used to pull the tailbone forwards and the ITs inwards so that the sacrum nods backwards.

In the case of the SI joint, stability can be achieved by using the transverse abdominus against the pelvic floor muscles. This may be why in a lot of cases, activating the pelvic floor muscles causes the Transverse Abdominus to activate and vice versa.

Sacroiliac Joint Muscle Activation Sequences

Following are some suggestions for learning to activate the transverse abdominus and the pelvic floor muscles.

Since these are muscles, they shouldn't be active all of the time. Indeed, if they are habitually active all the time, that can be a cause of problems... just as much of a problem is if they aren't functioning. And so a suggestion is that rather than trying to keep these muscles engaged at all times you instead practice activating them and relaxing them and getting familiar with both sensations.

Lower Transverse Abdominus

To activate the lower transverse abdominus focus on pulling inwards on the ASIS and optionally the inguinal ligaments while at the same time pulling your lower belly rearwards. The lower belly is the part of the belly below the line that joins the two ASIS (points of the hip bones).

Sacral Multifidus

To activate the sacral multifidus, practice lifting the tailbone relative to the pelvis. Rather than tilting the pelvis forwards to lift your sacrum, instead try to lift the back of your sacrum while keeping your pelvis relatively stable. You should be feel a "tightening" sensation at the rear of your sacrum as you do this.

Co-Activating Multifidus and Transverse Abdominus

Once you can control the transverse abdominus and multifidus in isolation you can experiment with co-activating them. Try activating the multifidus first and then the transverse abdominus and then try activating the transverse abdominus first and then the multifidus.

Pelvic Floor Muscles

To activate the pelvic floor muscles, practice drawing the tailbone towards the pubic bone. Then practice drawing the two sitting bones inwards after pulling the tailbone forwards. As you get familiar with the feeling of contraction in the pelvic floor that accompanies drawing the sitting bones inwards, try spreading the tension forwards in a fanlike shape towards the pubic bone. (Imagine the handle of the fan points towards the tailbone.

After the above actions, to create full tension in the floor of the pelvis, the pull the anus forwards, and then pull forwards on a point just in front of the anus. After enough practice you won't need to do these actions step-by-step. You can simply engage the muscles of the floor of your pelvis.

Integrating Sacroiliac Joint movements with Flattening the Lumbar Spine

Counter-nutating the sacrum can accompany a flattening of the lumbar spine (which can follow from tilting the pelvis rearwards.) The idea here would be to create tension along the floor of the pelvis and all along the front of the spine from the sacrum up to the top of the lumbar spine. In addition to the pelvic floor muscles this would also use the piriformis and psoas major muscles.

Basic Sacroiliac Joint Muscle Activation Sequence for Flattening the Lumbar Spine

A possible sequence of actions for flattening the lumbar spine could start with counter-nutating the sacrum.

- The first action could be to pull the tailbone towards the pubic bone and the sitting bones inwards.

- Following this the activate the piriformis by sucking the front of the sacrum forwards. This pear shaped muscle attaches from the front of the sacrum to the top of the thigh bone. When engaged it creates a forward pull on the sacrum. Either of these actions can start the pelvis tilting backwards so that the lumbar curve begins to flatten.

- From there then the psoas major can activate. This muscle attaches to the sides of the lumbar vertebrae and the intervening intervertebral discs as well as to the transverse processes. One possible way to activate the psoas it to create a forwards and downwards pull or suction on the sides of the lumbar spine.

- So that the Sacroiliac joints are controlled it may even be helpful to lead the above actions by activating the transverse abdominus first.

Actions where the lumbar spine can be naturally flattened can include the standing forward bend and the body weight squat or chair pose.

I say standing forward bend here because it has the advantage over the seated forward bend that the legs are easier to stabilize via the floor. In both exercises the hips are flexed bringing the front of the thighs towards the front of the pelvis and ribcage.

Standing Forward Bend

While holding a standing forward bend you can use the above sequence of actions. After activating the psoas major you may find that it's contraction helps to take you deeper into the forward bend. You may find that it feels good to activate the pelvic floor muscles first, then the transverse abdominus, then the piriformis followed by the psoas.

Body Weight Squat

For a body weight squat, you can do the activations while standing, maintain them while squatting down and while standing back up, then release at the top. For this I would suggest first activating the pelvic floor, then the transverse abdominus, then the piriformis and psoas major.

Sacroiliac Movements and Extending the Lumbar Spine

Nodding the sacrum forwards can accompany an increase in lumbar lordosis (which can accompany the pelvis being tilted forwards). Generally it can be difficult to move the legs rearwards relative to the pelvis. One reason for nutating the sacrum and then tilting the pelvis forwards (and backbending the spine) is that it can make it easier to swing one or both legs rearwards relative to the pelvis.

Basic Muscle Sequencing for Extending the Spine and Hips

As with flexing the spine and hip, the basic muscle activation sequence for extending the lumbar spine could actually start with contracting the lower transverse abdominus and creating an inwards pull on the ASISs. From there the following action could be to engage the sacral and then lumbar multifidus while at the same time tilting the pelvis forwards and bending the lumbar spine backwards. This could be useful in supine backward bending poses like bridge or wheel pose.

Bridge Pose

For bridge pose you can try the above actions while laying supine with knees bend and butt on the floor first. Then lift the hips while keeping the sacrum nutated and the spine bent backwards. Then carry the backward bend up into the ribcage.

Wheel Pose

Having practiced nutating the sacrum while supine and then in bridge pose, you can try to keep the action while resting with weight on the top of your head. Use your arms to lift your head up while maintaining the sacrum in nutation and while keeping the lumbar spine bent backwards.

The Sacrotuberous Ligament,

Gluteus Maximus, Piriformis and Hamstrings

In a forward bend, the gluteus maximus and hamstrings resist the weight of the body as you bend forwards at the hips. They can also be used to pull the body back upright when standing up from the forward bend.

In a body weight squat the gluteus maximus and hamstrings can be used to control the descent of the body by resisting the weight of the body. Then can then be used to bring the body back to standing.

In bridge and wheel pose the gluteus maximus (and possibly the hamstrings) can be used to press the hips up.

The gluteus maximus, piriformis and hamstrings (particularly the biceps femoris) all have attachments to the sacrotuberous ligament which runs from the Ischial Tuberosity to the sides of the lower part of the sacrum.

The sacrotuberous ligament tends to resist the sacrum being nodded forwards. Tension added to this ligament can also help to pull the sacrum into counter nutation.

The Hamstrings and the Sacrotuberous Ligament

Tension from the hamstrings, particularly biceps femoris, but also possibly from the semitendinosus and semimembranosus can increase tension in the ST (SacroTuberous) ligament. This means that whenever the hamstrings are activated they can help to stabilize the sacroiliac joints via the sacrotuberous ligament.

The Gluteus Maximus, Piriformis, and Sacrotuberous ligament

The gluteus maximus and the piriformis can also add tension to this ligament. What is important is whether the fibers that attach to this ligament attach from the sacrum to the ligament or from the thigh bone to the ligament.

Lets assume that they attach from the ligament to the thigh bone. If the thigh bones are stable then tension from these fibers can add tension to the sacrotuberous ligament helping to stabilize the sacroiliac joint.

At any rate, knowing the muscles that possible affect sacrotuberous ligament tension, one way to play with sacroiliac joint stability is to try activating these muscles while squatting or forward bending or doing wheel or bridge pose to notice there effects on the sacroiliac joint and the feel of the pose in general.

In all cases I would suggesting fixing the thighs in such a way that they resist being rotated. Then try to activate the muscles in question to notice their affect on the sacroiliac joint.

The Long Dorsal Sacroiliac Ligaments

The long dorsal sacroiliac ligament attaches from the PSIS, or rear of the hip bones, to the sacrum. The fibers of this ligament reach inwards and downwards from the pelvis to the sacrum. It has attachments to the sacral multifidus and the lumbar portion of the thoracic longissimus.

When the transverse abdominis activates, this ligament helps to resist the back of the pelvis being pulled apart. It also tend to resist counter nutation of the sacrum.

Tension in the sacral multifidus and thoracic longissimus adds tension to this ligament which then help to nutate (or resist counternutation) of the sacrum.

Note that if the sacrum is nutated, then this action will add tension to the sacrotuberous ligament. One of the ways in which this can be useful is that it gives the muscle fibers that attach there (the gluteus maximus, piriformis, hamstrings) a stable foundation from which to act. Thus if bending the spine and hips backwards, it may be best to start with nutating the sacrum (start with the transverse abdominus, then activate the multifidus) then bend the lumbar spine backwards. Then bend the hips backwards using the gluteus maximus and hamstrings.

Published: 2020 08 14

Updated: 2023 03 21