Long Hip Muscles

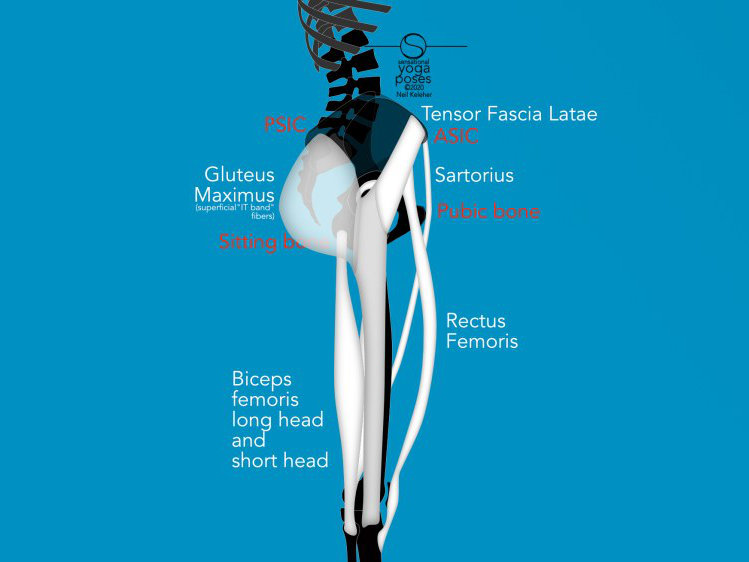

One way to stabilize the shins against rotation, and thus give the knees some stability is to use the long hip muscles. You could also think of these as thigh muscles, in particular those that act on both the hip joint and cross the knee to attach to the sides of the lower leg. Those include the muscles that work on or directly affect the IT band as well as the three pes anserinus muscles (sartorius, gracilis and tensor fascia latae), the semimembranosus and the biceps femoris.

Knee rotation is mainly noticeable when the knee is bent. That being said, there may be a slight amount of rotation possible even when the knee is straight. (I say that because I'm finding that I can actually create a slight amount of rotational movement of my shin relative to my femur when my knee is straight!)

This can be important to consider if you are dealing with problems like collapsed arches while walking, or a knee that tends to collapse inwards. And so with regards to these problems (which can be related), check out this article on the biceps femoris short head and how to anchor it: anchoring the biceps femoris short head.

Lateral thigh muscles that control knee rotation

Lateral thigh muscles that can help control knee rotation include the tensor fascia latae and the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus.

Both of these muscles attach from the hip bone (and in the case of the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus, possibly also the sacrum) to the iliotibial band which runs down the side of the thigh to attach to the lateral surface of the tibia.

Another set of muscles that could be considered lateral thigh muscles because they attach to the fibula are the short and long heads of the biceps femoris.

Superficial fibers of the Gluteus maximus

One possibility with the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus is that they attach to the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament. This ligament attaches from the inner surface of the hip bone, posterior to the sacrum. From there it reaches downwards to attach to the back of the sacrum.

The sacral multifidus attach to or otherwise can affect this ligament. Likewise, the longissimus muscle which is part of the spinal erector group.

It may be that a portion of the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus attach to this ligament, or they all do. In any case, tension in this ligament, created by tensioning the lumbar multifidus or the longissimus or both can help to anchor the fibers of the gluteus maximus that attach to it leading to better rotational stability and rotational control of the knee joint.

Note that tension in this ligament may also have an affect on hip joint stability as well.

A simple means of adding tension to this ligament is to tilt the sacrum forwards relative to each hip bone. The feeling can be as if lift an imaginary tail. Once having a feel creating tension at the back of either SI joint, the practice can then be that of creating this tension at will. From there, the next stage of practice can be simply to activate the gluteus maximus on the targeted side. Hip rotation and ribcage positioning can have an affect on the ability to add tension to this ligament, and so while learning to apply this tension, part of the process can include learning to adjust hip rotation and ribcage positioning.

Tensor fascia latae and superficial gluteus maximus

Tensor fascia latae attaches from the ASIC (the point of the hip bone) and runs downwards and backwards to attach to the front edge of the IT band.

The superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus attach to the back edge of the hip bone (and possibly the sacrum), running forwards and downwards to attach to the rear edge of the IT band.

Standing upright, the tensor fascia latae can be used to rotate the shin internally. The superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus can be used to rotate the shin externally.

Controlling internal and external knee rotation with the knee bent or straight

Note that because knee rotation relative to the femur is severely limited when the knee is straight, the tensor fascia latae can be used to help internally rotate the shin and thigh together. Likewise the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus can be used to externally rotate the shin and thigh together.

With the knee bent, it seems like that the tensor fascia latae and superficial gluteus maximus maintain the same functionality. The former can continue to be used to rotate the shin inwards while the latter rotates it outwards.

Sitting on a chair with feet on the floor, or positioning the legs in a lunge with one leg forwards, knee bent, and the other leg back, what this can translate to is that the tensor fascia latae can be used to move the knee outwards while the superficial gluteus maximus can be used to move the knee inwards.

These muscles can also be used together to help stabilize the knee in these positions, whether it is inwards, outwards, or somewhere in between.

Biceps femoris

The long head of the biceps femoris attaches from the sitting bone, runs down the back of the thigh before attaching to the top of the fibula. The short head of the biceps femoris also attaches to the top of the fibula. However, the upper end of this muscle attaches to the back of the thigh.

Both of these muscles can help to externally rotate the shin by creating a rearwards pull on the fibula.

Note that the biceps femoris short head, because it attaches to the femur, acts to help control external rotation of the shin relative to the thigh. Meanwhile, the long head, because it attaches to the hip bone (at the ischial tuberosity or "sitting bone") can control external rotation of the shin relative to the hip bone.

As with the tensor fascia latae and superficial gluteus maximus, if the knee is straight, then the long head of the biceps femoris can help externally rotate the shin and thigh bone together relative to the hip bone.

Medial thigh muscles, the pes anserinus and knee rotation

Medial muscles that help to control knee rotation include the sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus which attach join together near their attachment to the inside of the tiba to form a structure termed the pes anserinus or "goose foot". Note that the semimembranosus, may or may not play a role in controlling knee rotation.

Sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus

All three of the pes anserinus muscles attach to prominent corner points of the hip bone.

Sartorius attaches to the ASIC. From there it runs down the inner thigh, in front of the adductors and then behind the vastus medialis before attaching to the inside of the tibia.

Gracilis attaches near the pubic bone. From there it runs down the inner thigh to attach to the top of the tibia.

Semitendinosus, along with the other hamstring muscles, attaches to the ischial tuberosity (sitting bone). It runs down the inner edge of the back of the thigh to attach to the inside of the tibia.

Sartorius and knee rotation control

Because of the way that the sartorius curves behind the knee joint, when the knee is straight it can be used to externally rotate the shin and femur relative to the hip bone. Note that the knee needs to be stabilized for it to act in this regard. With the knee bent, the sartorius can act to rotate the shin internally relative to the thigh bone. However, if the shin is stabilized against rotation with the knee bent, the sartorius could be used to help flex the hip. It can also be used to flex the hip if the knee is straight.

Gracilis and semitendinosus and knee rotation

With the knee bent, gracilis and semitendinosus can be used to rotate the shin internally relative the to the femur (thigh bone). With the knee straight, these muscles can be used to rotate the thigh and shin internally relative to the hip bone. Note how with the knee straight these muscles can work against the sartorius to help control rotation of the leg relative to the hip bone.

Anchoring the long hip muscles

All of the long hip muscles attach to corner points of the hip bones (the ASICs, PSICs, pubic bone and sitting bone). So that these muscles can work effectively to control rotation of the shin relative to the hip bone, it helps if the hip bone is stabilized or anchored to resist whichever long hip muscles are being used.

If the hamstrings and/or superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus are the main focus, then it can be desirable to create an upwards pull on the back of the hip bones to anchor those muscles. If the muscles that attach to the pubic bone or ASIC are the main target then it can be desirable to create an upwards pull on the front of the hip bones.

With the hip bones anchored, the anchored muscles can be used to stabilize or control knee rotation in turn giving muscles that across the knee joint a foundation from which to help control rotation of the thigh bone relative to the lower leg bones.

Knee rotation and controlling the foot arches

With respect to the feet, (and with the feet on the floor) knee rotation generally causes a change in shape of the inner arch of the foot.

Rolling the shins outwards tends to accentuate the arch while rolling them inwards tends to flatten it.

While this can be driven by the aforementioned thigh muscles, it can also be driven by muscles that attach from the bones of the lower leg and cross the ankle to attach to the bones of the feet.

Integrating knee rotation options

While it can be helpful to train both in isolation, rotating the shins while standing and using the muscles of the foot, and then rotating the shins (again while standing) while using the afore mentioned thigh muscles, the goal should then be in integration.

One scenario is to use the thigh muscles to control rotation of the shins so that the muscles of the feet and ankles can effectively control the shape of the feet. The knee can also be protected by using single joint muscles to control the thigh relative to the lower leg bones.

Another is to use the muscles of the feet and ankles to control rotation shaping of the feet and knee rotation so that the thigh muscles can be used to help stabilize the hip bones. Here too, single joint muscles that work across the knee can be used to control the thigh relative to the lower leg bones.

Learning and practicing both can make it easier to prevent problems at the knees as well as at the feet and hips and ideally getting them working well together so that you can do whatever it is that you want to do with impunity.

Knee rotation and doing yoga poses

Note that with respect to yoga poses, knee rotation control is extremely helpful if you want to keep your knees, hips and feet safe while working towards virasana, lotus, the janu sirsasana series and potentially even when working on both side splits and front splits.

Published: 2020 08 04

Updated: 2023 04 02